First published Winter 1995

The first part of this Newsletter is about seafaring Cuddefords. These stories are compiled from public records, or from the accounts sent in by Cuddeford friends. The second part, continuing a series of articles about sources of genealogical information, is not reproduced here as, although it of general interest, it does not specifically concern Cuddeford family history.

Henry Charles Cuddeford

“Harry” Cuddeford was born on 21st August 1909 at Smethwick, in Birmingham. However, his ancestry lies in Devonshire, his father, also Henry Charles Cuddeford, travelled to Birmingham from Plymouth. Harry’s Grandfather was 30 years at sea under sail, mostly in the South American meat trade. His father was the skipper of a barque out of Plymouth. Harry has perhaps the longest family seafaring tradition of all of us.

Harry himself joined the Royal marines in 1927 but soon transferred to the Royal Navy in 1928. He served at sea in a variety of warships starting in 1928 in HMS Marlborough, a Battleship in the Home Fleet. Then, in 1930, he joined HMS Saltash – a Mine-sweeper (quite a change from a battleship!). Then followed service from 1931 to 1934 in HMS Kent, a Cruiser on the China Station. After that it was another Battleship, the mighty HMS Renown in the Mediterranean. After HMS Renown, came service in three Cruisers. HMS York from 1936 to 1939, in HMS Berwick until 1940; both ships were part of the America and West Indies Squadron. From 1940 Harry was in HMS Cleopatra and took part in the dangerous work of running the Malta Convoys. This until 1943 when he found himself in another Battleship HMS Anson, part of the British Pacific Fleet. This was the first British ship into Hiroshima after the atom bomb. Finally. the last two years of his service were spent in a shore base. He retired to pension in 1949. His work was as a Marine Engineering Mechanic and he achieved the rank of Chief Petty Officer.

In civilian life he was engineer in charge of a local factory and retired from that at the age of 65. In retirement, Harry and his wife, lived in Surrey and enjoyed gardening and wine-making, he passed away in 2002 aged 92.

Harry said that he counted himself a lucky man in many ways. Once, when he was with HMS Berwick in Bermuda, he was offered the chalice to travel home for a course which could have led to promotion. However, Harry, being a cheerful and sociable fellow, decided to stay with his circle of friends in Bermuda and turned down the chance of a voyage home in SS Penzance. Just as well because that ship was sunk by the German Pocket Battleship “Deutschland”. On another occasion, whilst helping to prepare HMS Cleopatra for sea and living in lodgings in Wallsend, Harry escaped in his pyjamas when the house next door was bombed.

His third and most dramatic escape is described in his own words in an article for a local magazine celebrating “Victory – 50 years on” – “The Day I nearly Died”

It was dark, with a medium sea running in the Gulf of Messina, on the 17th July 1943. We were on HMS Cleopatra of the 14th Cruiser Squadron. On our flank was the “Eurylus” with an assortment of destroyers and assault and landing craft between. The only thing to be seen was an occasional flicker of phosphorescence as some craft breasted a wave. We were the spearhead of the long awaited landings in Italy. After 18 months of Malta Convoys, bombarding the North African coast road, an attack on Rhodes and, finally, the Battle of Sirte, this operation ought to be a piece of cake.

I left the upper deck after taking a few breaths of fresh air before turning in. I should get a couple of hours sleep before taking over the morning watch as Chief in “A” boiler room – unless “Action Stations” sounded. As I entered the mess, quiet except for the usual ship’s noises, I saw in the dim light someone leaning on a table, head in hands, moaning softly. It was my opposite number and relief in “A” boiler room. “Hello Albert” I said. “Can’t you sleep?” He raised his head, his unshaven face haggard, dark rings round his eyes. “Sleep?” he groaned. “I haven’t slept for days. It’s this bloody tooth. Its driving me mad”. I muttered a few words of sympathy and made to move on. He grabbed my arm and said “If I do your morning watch will you swap and do my forenoon one, then I can see the Doc at 0900 Sick Quarters. He will probably take the damn thing out or give me an injection. What do you say?”

One four hour watch below is much the same as any other. One got inured to the roar of the oil fired furnaces and the deafening blast of the forced draught fans. I agreed, so he could get help and I would gain a little more rest.

“Action Stations” sounded at 0600 and we tumbled out. I had barely arrived at my Damage Control action station amidships when there was a terrific bang. A blast of hot air and smoke whipped through between decks. The ship took a frightening list to starboard and then slowly righted herself. The lights went out. We clawed our way to the upper deck. It was broad daylight. We had been torpedoed. There were a few casualties here and there and a small fire had been dealt with but both “A” boiler room and “A” engine room were flooded, the ship was at a standstill and the upper deck was about four feet above the waterline. We were no longer an active unit.

Luckily, the “B” units were still operational so, provided the bulkheads held against the enormous amount of water we had taken in, by pumping the remaining fuel from the forward tanks to the after tanks, we should be able to creep back to Malta for repairs. With a destroyer escort. the journey took two days and luckily we were not attacked.

At Malta we entered the only serviceable dry dock and drained down. Damage was considerable but repairable. Then came the awful job of removing the bodies.

The impact of the torpedo had exploded the boilers and with steam at 1200 degrees(F) the human body rapidly loses its identity. The stench was unbelievable. Later I attended the sea burial of my shipmates. When it came to Albert’s turn the thought hit me with tremendous force, had it not been for a rotten tooth, it would have been me going down the slope, under the White Ensign, into the blue Mediterranean.

Victory – 50 years on – The Day I nearly Died

Benjamin Robert Cuddeford

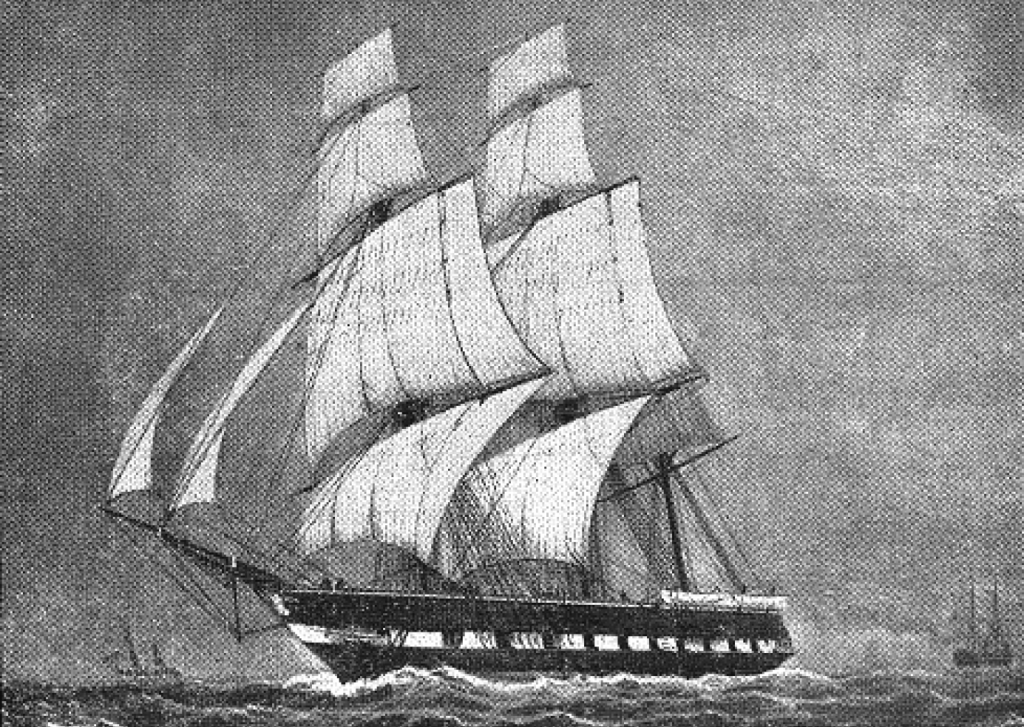

At Bonchurch on the Isle of Wight at about 3 p.m. on 24th March 1878 the coastguards sighted HMS Eurydice sailing up-channel with all her sails set. She was on course to anchor in Spithead before dark at the end of her voyage from Bermuda. She was a 960 ton, full rigged 26 gun frigate built at Portsmouth in 1842 and was then in use as a training ship. On that day she had on board her own ships company of 330 men and boys as well as 58 passengers, military officers and invalids from the West Indies Station. She had come to the end of a successful training cruise.

It being a Sunday afternoon, all her hands except those on watch were enjoying a “make and mend”, that is, an afternoon to amuse themselves as they wished. Most of the ship’s company were below decks either sleeping, mending clothes, reading or writing letters home.

It was a fine Spring day and Eurydice was bowling along at about 10 knots with a following wind. The gun ports were open to help ventilate the lower deck. A heavy cloud was building up over the Isle of Wight but was hidden from the quarterdeck by a hill. Ahead, the sea was calm and there was no sign to cause alarm. Suddenly, without warning, the wind changed through 180 degrees and became a blinding snowstorm. The Eurydice was caught flat-aback by this violent headwind, her sails forced backwards against the spars and masts. Despite efforts to loosen the sails, the ship took a steep list to port until the sea began to pour through the open gun ports. The lower decks flooded immediately . Still moving forward she drove herself deeper into the sea and soon disappeared below the waves. There were two survivors. One was Able Seaman Benjamin Robert Cuddeford.

Benjamin was quoted in The Times newspaper of 26 March 1878:

Prior to leaving Portsmouth, Cuddiford made an important statement to Admiral Foley of the circumstances attending the wreck. He said :- “At 7 bells on Sunday afternoon, the 24th inst., the watch at a quarter to 4 o’clock was called to take in lower studding sails. I was on deck to tend the lower tack, and let it go. The captain gave orders to take in the upper sails. The wind was then freshening. The captain ordered the men to come down from aloft and then to let go the topsail halliards. The gunner’s mate let go the topsail halliards, and another man, Bryant, let go the mainsheet. The water was then running over the lee netting on the starboard side, and washed away the cutter. The foretopmast studding sail was set. The wind was about a point abaft the port beam. I caught hold of the main truss, fell, and caught hold of the weather netting and got on the ship’s side. We could see her keel. She righted a little before going down, ringing the mizzen topsail out of the water. She then went gradually over from forward, the greater part of the hands being at the fore part of the ship outside. She then turned over, bringing the port cutter bottom upwards. I and another, Richards, cut the foremost gripe, and then saw the captain standing on the vessel’s side near the quarter boat and the two doctors struggling in the water. I swam some distance, keeping over my head a lifebuoy, which I found, and then picked up some piece of wreck, which I gave to some of the men in the water. I then came across the copper punt full of water, five men were in it. The sea capsized the punt, and they all got on the bottom. They asked me if there was any signs of help. I told them the best thing they could do was to keep their spirits up. One of them was just letting go his hold of the punt. I do not know his name. I next saw Mr. Brewer, the boatswain, with a cork lifebelt on. He was struggling strongly. I then saw Fletcher in the water with a cork belt and breaker. I lost sight of him during the snow. About five minutes afterwards the weather cleared up. I saw Fletcher again, and we kept together. Then we saw land, but, finding it too rough, we turned our backs to the land and saw a schooner. The schooner bore down on us, sent a boat, and picked up two officers that I had not previously noticed with a wash-deck locker. A rope’s end was thrown to me from the schooner, and I was then picked up. I judge that I was in the water one hour and 20 minutes. The officers picked up were Lieutenant Tabor and a captain of the Royal Engineers who came on board at Bermuda with one corporal, one bombardier, four privates, and the servant of an officer of the Royal Engineers. The ship capsized about 10 minutes before 4 o’clock. The captain was giving orders at the time, and was carrying out his duty, We rounded on the weather beam, and set the lower studding-sail, at 2 p.m. The ship was then going 8½ knots. I don’t know who was the officer of the watch, as the captain was carrying on the duty. The Hon. Mr. Giffard went to the wheel to help at the time the water was coming over the lee nettings in consequence of an order being given to put the helm up. There were the following supernumeraries on board :- Three Court-martial prisoners from the Rover; one A.B., a Court-martial prisoner from Bermuda; an ordinary seaman named Parker, who had been tried by Court-martial (he belonged to the Eurydice); and about 12 or 14 Marines, with one sergeant of Marines from Bermuda Dockyard, two invalids from Bermuda Hospital, one ship’s corporal from the Argus, one captain’s cook from the Argus, one engineer’s steward from the Argus, one ship’s cook from Bermuda Dockyard, one quartermaster, named Nicholas, from the Rover. I believe some of the maindeck ports were open to let in the air to the main deck mess. I don’t think the hands were turned up; there was hardly time for that. I saw most of the men forward take off their clothes and jump off before I lost sight of them in the squall. When the snow cleared up the ship was gone down.”

The Times 26 March 1878

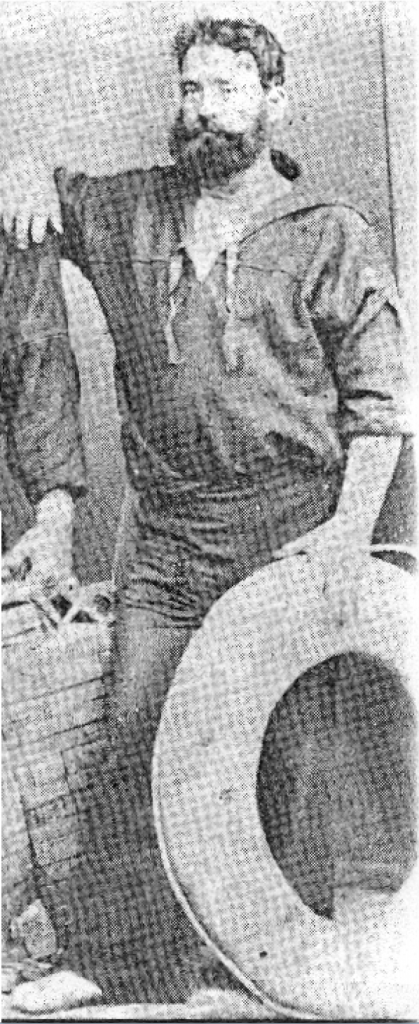

Benjamin was born on 5th December 1842. His parents were James and Elizabeth Cuddeford of No.10 Gloucester Street in Morice Town, Devonport. His father was a carpenter. Benjamin joined the Royal Navy on 11th September 1857 as a Boy Seaman 2nd Class. He was then nearly three months short of his 15th birthday. He signed on for ten years service from the age of 18. He was described as 5 ft 8 inches tall, of fresh complexion, light hair and grey eyes. Later he acquired a tattoo on his chest!. He claimed his occupation was “Artist”. He was serving in his fourth ship , HMS London, when he reached 18 and was rated Ordinary Seaman and eventually an Able Seaman.

Service in three more ships brought him to the end of his engagement. During that time he had a somewhat chequered career. He seems to have fallen foul of the Naval Discipline Act and found himself in detention twice. Once in Devonport for 28 days and again in Malta for 42 days. His character assessment started as “Very Good” and dropped to “Indifferent”. However, he seems to have rehabilitated himself and regained his “Very Good” character when his ten year engagement came to an end.

He then signed on for a second ten years and served in half a dozen more ships, including

HMS Eurydice, before being invalided to pension in August 1879. During this time he was twice briefly rated Leading Seaman and then Petty Officer. These appear to have been temporary promotions as his substantive rating remained as Able Seaman. Benjamin died a bachelor at the age of 38 leaving no Will. His widowed mother was still alive but it was his brother James who handled Benjamin’s estate. It was valued at £265.

Charles Cuddeford

Early in the morning of Friday 24th November, 1848, the Brig “Sea Witch” on a voyage

from Africa to London was totally wrecked on the rocks of Portinfer Bay on the north west coast of Guernsey in the Channel Isles. She was on the final stage of her voyage from Sierra Leone with a cargo of African Oak and groundnuts for the manufacture of oil. There were only three survivors. The Master and seven of the crew were drowned, among them was Charles Cuddeford.

The funeral of the victims took place on the following Sunday when the coffins were carried two miles to the Church at Vale, the nearest village. So many people followed, that the procession was nearly half a mile long. Some ten or twelve thousand local people attended the funeral service at the church where the men were buried in a common grave in the churchyard.

Charles was born on October 26th, 1828 and therefore was just 20 years old when he lost his life. His parents were Robert Cuddeford, a stone mason, and Ann his wife. (Incidentally, they were also the Great-great-grandparents of Harry Cuddeford (see above). This was not Charles’s first voyage. In November 1844 at the age of 16, he signed on for the Schooner “St.Vincent” as an apprentice and made three voyages in her. In November 1847, he sailed in the “William Wilberforce” from Cardiff to Cartagena in the Southwest of Spain, and Villa Nova in the North of Portugal. He returned to London on 22nd April 1848. It seems that he was Mate on this sailing as his name appears after that of the Master and all the rest of the crew were younger.

(Grateful thanks and acknowledgement to Mrs Phyllis Matthews who supplied the details of Charles’s career and of the loss of the “Sea Witch.)

Thomas Cuddeford

Thomas Cuddeford was born on Monday 22nd July 1844 in Plymouth. His parents were Edward Cuddeford, a successful butcher, and his wife Mary Ann. Thomas studied medicine and qualified on the Medical Register in December 1867. He was a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons and a Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries. He practiced for a time in London at St Bartholomew’s Hospital and lived in New Bond Street.

At some stage he joined the Union Company’s Steam Ship “American” as ship’s surgeon, and sailed from Plymouth on 17th December 1874 bound for the Cape of Good Hope. On arrival at St. Helena on Saturday 2nd January 1875, Thomas was taken seriously ill with brain haemorrhage and died very quickly.

He was buried the next day in the rural cemetery of St Paul’s Cathedral. A gravestone exists with the inscription “To the Memory of Thomas Cuddeford, Surgeon of Plymouth.”. There is also an inscription to his memory on the family grave in the cemetery at Egg Buckland in Plymouth.

Frederick William Francis Cuddeford

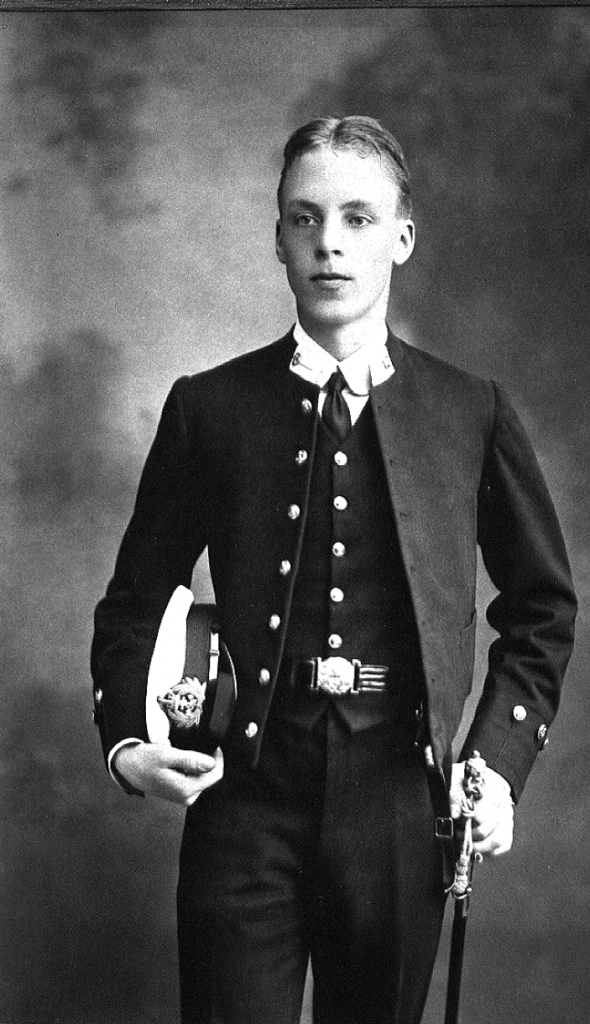

“Frank” Cuddeford, the second son of William and Mary Cuddeford, was born at Chester on Sunday 18th February 1894. Educated at Bedford School, he joined the Royal Navy as a Cadet in January 1907. He trained at the RN Colleges at Osborne and Dartmouth and joined the fleet as a Midshipman in January 1911.

He served in HMS Formidable, Cumberland and Commonwealth before being commissioned as a Sub Lieutenant in 1914. From then until 1917 he served in HMS Carnarvon, a cruiser of the 5th Cruiser Squadron.

On 7th December 1914, a force consisting of the battleship HMS Canopus; two battle cruisers, Invincible and Inflexible, and several cruisers, including Carnarvon, arrived at Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands. They had been sent to seek the German Asiatic fleet which was expected to round Cape Horn in an attempt to return to Germany. The German force consisted of the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, the cruisers Nurnberg, Leipsig and Dresden and several supply ships.

Early the following morning, the Germans were sighted approaching the islands, clearly unaware of the presence of the British fleet. On sighting the smoke of the British ships, the Germans turned to the east followed by all the British ships. A long running battle ensued and by 4 p.m. that day all but one of the German ships had been sunk; only the Dresden escaped.

Frank Cuddeford, a Navigating Officer in HMS Carnarvon, was on the bridge throughout the action and that evening he wrote a full account of the battle which remains with the family today.

On leaving HMS Carnarvon in 1917, by now a full Lieutenant, Frank volunteered to join the submarine branch. He served in several submarines of various classes before joining HM Submarine K.5 as Second-in-Command in January 1921.

On 20th January, 1921, K.5 was taking part in manoeuvres with the fleet in the Channel. She dived at 11.30 am but failed to surface at the allotted time. A search revealed oil and some debris on the surface close to where she dived. No reason for this accident has ever been found. There were no survivors.